“The Disputed Territory”: the story of the St. Croix border

by John G. Kelly

This article is the first in a new series from the Charlotte County Archives dedicated to stories drawn from the documentary heritage of Southwest New Brunswick.

The Canada/ United States (U.S.) border has become a much talked about political topic concerning the issue of illegal border crossings between two countries that take pride in sharing the longest undefended border in the world. However, many Canadians and Americans are unaware of the pioneering role that Passamaquoddy Bay and the St. Croix River played in setting precedent for resolving border disputes peacefully through negotiation and arbitration, a model for border dispute resolution in the modern era.

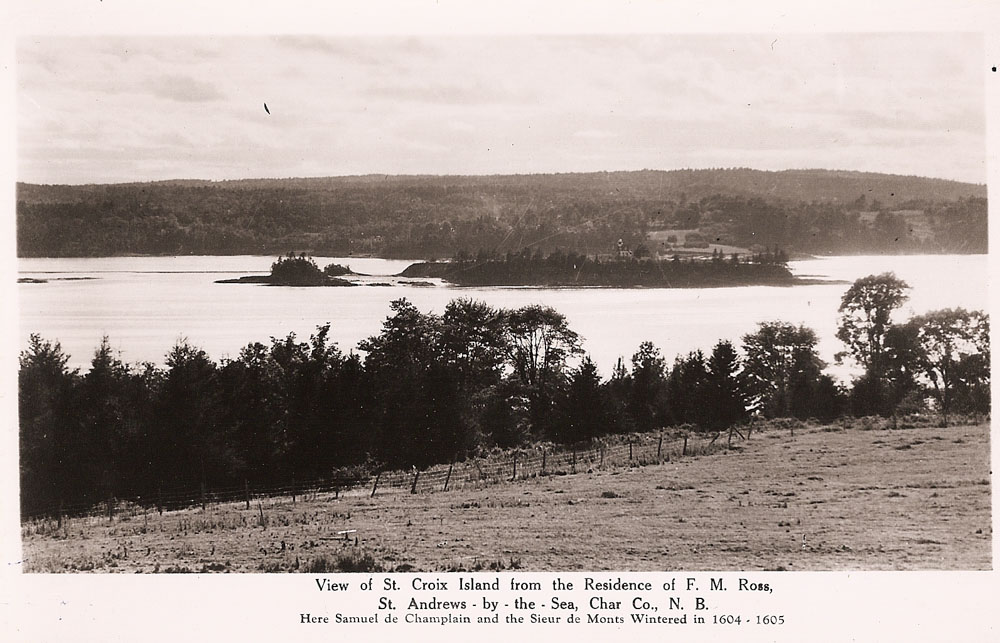

A French expedition including Samuel de Champlain established the first permanent European presence in what is now the Bay of Fundy. In 1604 Champlain named a river that flowed into Passamaquoddy Bay as the St. Croix. The expedition set up a colony on the river that is today labelled as St. Croix Island, abandoned only a year later. By 1632 all traces of the settlement had disappeared.

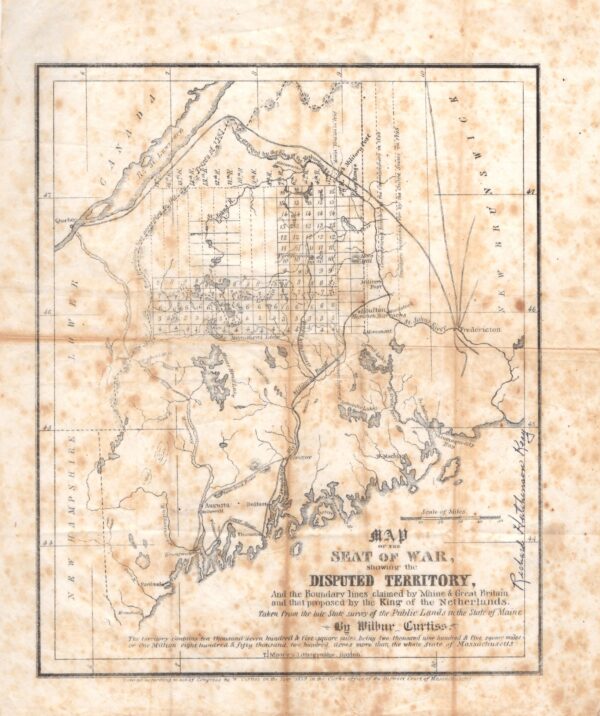

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the American Revolution and defined the boundaries between the U.S. and Britain. The treaty specified that the boundary between the U.S. and Britain would commence at the “northwest angle of Nova Scotia” (now New Brunswick) with a line that joined Passamaquoddy Bay to the mouth of the St. Croix River. The boundary would then extend along the midpoint of the river to its point of origin in the vicinity of the St. Lawrence River.

“…from the Northwest Angle of Nova Scotia, viz., that Angle which is formed by a Line drawn due North from the Source of St. Croix River to the Highlands…”

What was the exact location of this Northwest angle? What was the impact of a straight line that randomly cut through a series of small islands in Passamaquoddy Bay? Where did the Passamaquoddy Bay end and the St. Croix River begin? And finally, which of the several rivers that emptied into Passamaquoddy Bay was the actual St. Croix named by Champlain?

Not surprisingly, a debate ensued with the potential to reignite armed conflict between the American and British colonists. In order to peacefully resolve these disputes Britain and the U.S. signed the Jay Treaty in 1794. It sought to settle outstanding issues, prominent among them being trade, border and boundary disputes between the two countries that had been left unresolved since the American War of Independence.

A commission composed of American and British members was set up to resolve the St. Croix boundary dispute, using comprehensive land surveys and site visits to determine what river was most closely associated with the records of Champlain and the source of demarcation from the bay to that river.

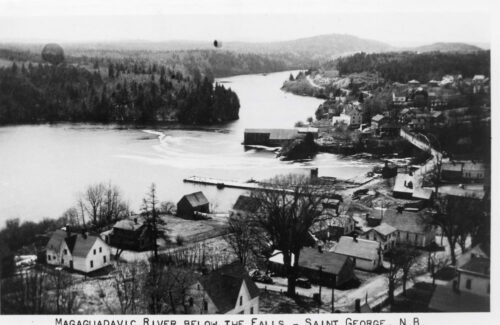

The American position was that the actual St. Croix River was the Magaguadavic River, which extended from the Passamaquoddy into the centre of New Brunswick. This would have extended the boundary into the proximity of Fredericton, a considerable loss of land for the British.

Fortunately for the British, the French archives had a copy of Champlain’s map of the St. Croix River. The British utilized this official map as a guide to an island then known as Douchet’s Island. An early archaeological excavation lead by St. Andrews’ Robert Pagan uncovered ruins that could be clearly linked to the French settlement circa 1604/1605. The Americans conceded that this was in fact the true St. Croix River and should be used as the source of the line.

Once the location of the St. Croix River was determined it was necessary to decide where it emptied into Passamaquoddy Bay. Where was the actual boundary of the St. Croix River? The midpoint of the river where it emptied into the bay was where the line was to be drawn and extended northward.

Two locations were up for discussion. One was Devils Island adjacent to the American shore in proximity to Eastport, technically in the Bay of Fundy. The other was Joe’s Point on the shore of the Passamaquoddy, on the edge of the town of Saint Andrews. Once again, archival records were relied upon to settle the dispute. Champlain’s notes indicated that Joe’s Point, not Devil’s Island, was the location he utilized as the source for the St. Croix River. As part and parcel of an exchange wherein Britain was granted full ownership of Deer Island and Grand Manan, with Campobello remaining with Britain and Moose, Dudley and Frederick Islands being ceded to the U.S., Joe’s Point became the agreed upon point of origin for the St. Croix River.

A survey starting at Joe’s Point and following the middle of the St. Croix River resulted in St. Croix Island being 116 Rods (1,856 feet) off the shoreline of Wilson’s Point on the American side and 176 rods (2,816 feet) off the New Brunswick shoreline. The shore of the island was 960 feet closer to the American border. Had Devil’s Island been the agreed upon source St. Croix Island would have been in Canadian territory.

The border issues negotiations were incorporated into the Treaty of Ghent, the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 and took effect in 1815. A provision in the treaty put a process in place to finalize the boundary issues initially set forth in 1783, though it was only in 1842 that Britain and the U.S. signed the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which became the definitive agreement for the resolution of all boundary and border matters. The joint commission approach became the foundation for the U.S. and Canada to successfully resolve cross-border and boundary issues for more than 200 years.

But—and so often there is a but when it comes to complex international boundary issues—in 1896 the Province of New Brunswick passed provincial legislation that erroneously included St. Croix Island within the boundaries of New Brunswick. In 1899 this legislation was amended to acknowledge U.S. ownership. Just to make certain that there would be no additional misnomers on the issue in 1908 the U.S. government erected a stone monument on Joe’s Point on the St. Andrews shore with a plaque clearly stating that this was the U.S./Canadian government agreed-upon source of the St. Croix River.

Dig up your own stories from the collection of the Charlotte County Archives! We welcome researchers of all varieties, from keen grade school students to casual history buffs to dedicated academics. See here to learn more about research.

John G. Kelly is a retired law professor and author of Meaningful Memories – Rekindling Past Learning Experiences to Live Life to the Fullest.